The Inflation Reduction Act (“IRA”) is the largest legislative effort in U.S. history designed to accelerate the country’s transition to an alternative energy and climate future. This Act is remarkable not only for its ambitions but for its disproportionate reliance on tax incentives, a fundamental difference in structure from other Biden era legislation like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. A community hoping to maximize the value of IRA funding will need to organize networks of beneficiaries, intermediaries, and stakeholders in ways that integrate areas of practice (e.g., renewable energy, talent preparation and housing development) that are often kept separate and distinct.

This newsletter identifies 6 central strategies that, if implemented well, could harness the multi-sectoral and inter-disciplinary networks that are key to IRA success.

The Inflation Reduction Act: A Study in Difference

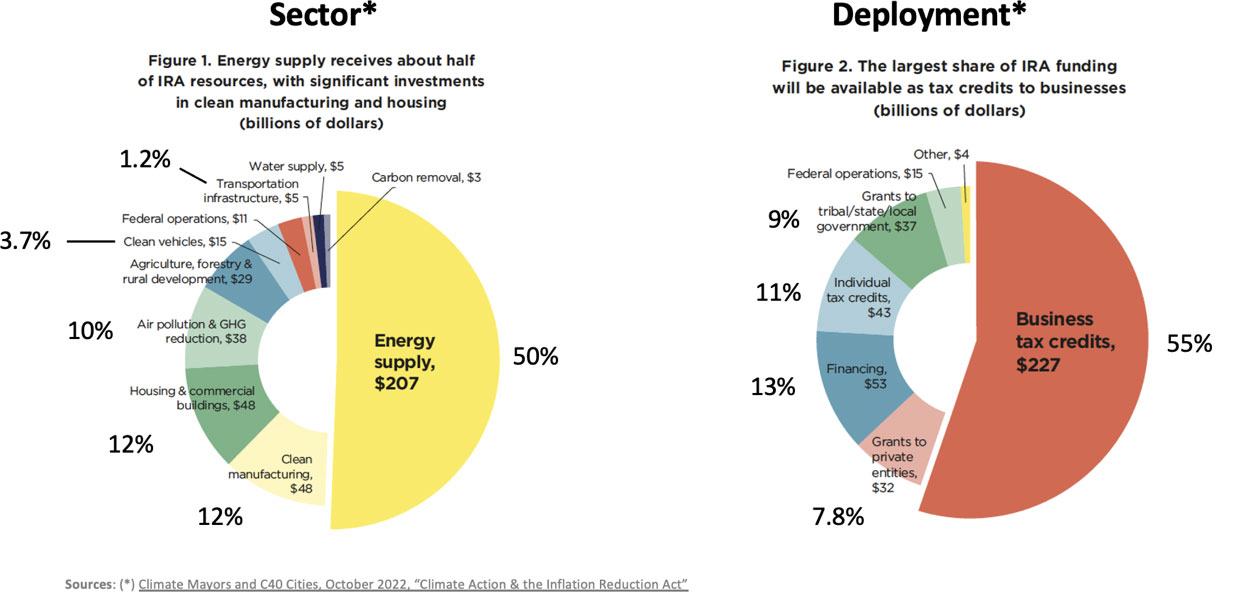

The IRA is a remarkable exercise in national economy shaping. With $411[1] billion in climate- and resilience-related funding, it aims to remake the nation’s energy future by providing incentives to produce clean energy, manufacture clean energy supply chain products, build and retrofit energy efficient (and renewably sourced) commercial buildings and homes, incentivize electric vehicles (EVs), convert auto supply chains into EV supply chains, reduce carbon from energy-intensive industries like cement and transportation, reduce air pollution generally and near schools, and mitigate other natural hazards while also promoting climate resilience. It significantly tries to do all these things with both an explicit focus on environmental justice and a clever use of market incentives by sweetening the value of tax returns for those who can align their projects to key societal goals (e.g., paying workers well, locating projects in low-income communities or legacy fossil fuel communities).

To this end, the IRA both has a different set of beneficiaries and a different toolkit of benefits from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (and, indeed, most federal appropriations). Most of its funding is allocated through tax incentives to private companies or private individuals rather than grants to states, cities, counties, or other public entities (e.g., ports, airports, schools, etc.).[2] A full 55% ($227B) of its $411 billion in funds go directly to business, and another 10% ($43B) to individuals, all in the form of tax credits. And, if you add in the grants to private entities (some of which are designated for nonprofits, but others for businesses), fully 73% of this funding is NOT designated for state or local governments.

Indeed, only a mere 9 percent of IRA ($37B, primarily climate and resilience) funding is directly allocated to a combination of local governments, counties, states, and tribes.[3]

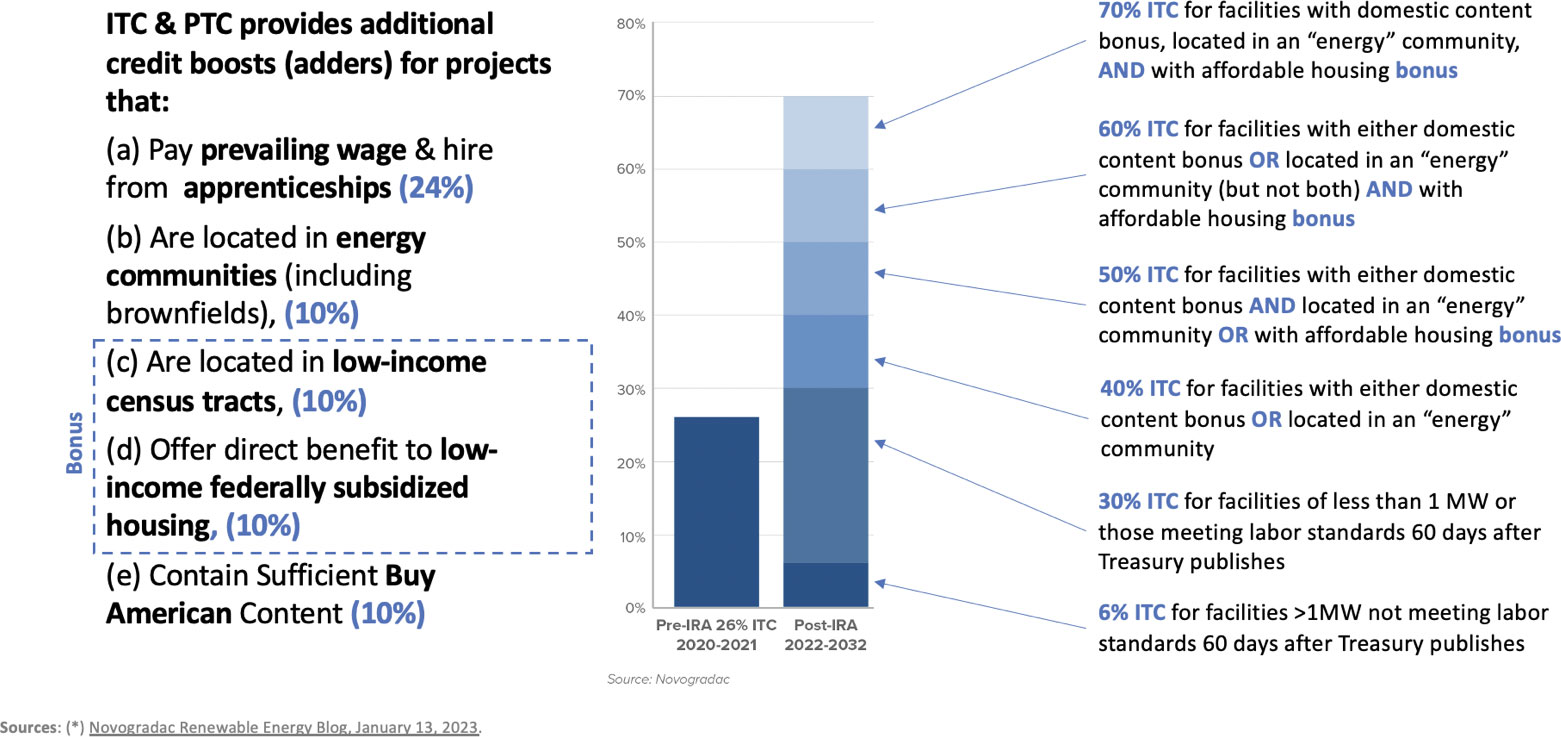

The IRA also differs markedly from prior tax incentives. The tax incentives in this legislation contain a series of “adders” that expand the value of the incentive that benefit and include certain populations or places. Additional benefits accrue from, for example, using apprenticeship program workers, or paying workers prevailing wages, locating projects in a low-income or legacy energy community or brownfield location, Buying American, and/or serving an affordable housing development. These tax credits can total as much as 70 percent of the qualifying project costs. This graphic shows how the tax credit grows in value as these social purposes are achieved:

And, for the first time, not-for-profit institutions, like universities and hospitals, and local and regional governments, can obtain tax credit benefits through direct payments from the federal government for qualifying clean energy or efficiency projects. Commercial building owners and homeowners also have access to these more robust tax credits, deductions, and rebates to add renewables or improve the efficiency of their new or existing buildings.

Finally, many ordinary consumers are now eligible to save thousands of dollars via tax credits or efficiency rebates when they buy products (e.g., an electric vehicle, a heat pump, solar panels, or energy-efficiency appliances) that are proven to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Maximizing the IRA

Given the structure of the IRA, organizing for success will require communities to undertake a series of actions aimed at different kinds of beneficiaries. At the outset, it must be recognized that the capacity of localities and urban and metropolitan networks are not aligned with the scale of federal funding or the tasks at hand. Most communities simply do not have the personnel with the capabilities, competencies, or bandwidth to plan transformative projects, apply for disparate federal sources, do the capital stacking necessary to make catalytic projects happen and coordinate multiple stakeholders for synergistic effect. Indeed, the 55% of the funding that is targeted to business tax credits will disproportionately benefit those communities which can give renewable energy project developers (and, indirectly, their investors) easy access to skilled workers or relevant projects in low-income communities (a solar array on housing development, or community solar).

We recommend the following 6 actions:

1. Establish a Climate Projects Action Team

The IRA is intended to benefit a range of individuals and organizations which design and deliver very different kinds of projects. Cities (in close collaboration with counties and the state) should set a table where intended beneficiaries (e.g., manufacturers, energy project developers, building owners, industry) and helpful intermediaries (e.g., utilities, business leadership groups, skills providers) can work together to design, capitalize, and execute projects while also aligning those projects for maximum inclusive and sustainable impact.

In geographies with large numbers of projects or participants, such teams can set up task forces that align with the key organizing elements of the law (e.g., around buildings, clean manufacturing, and industry). This effort should leverage existing structures or partnerships wherever possible, such as local Workforce Investment Boards that bring together employers like manufacturers with workforce training providers. Tax-exempt institutions (e.g., universities, hospitals, governments), for example, would be a natural sub-group such an effort.

The Climate Projects Action Team can start the process of unlocking the full value of tax credit “adders” by organizing across sectors to identify target real estate in certain communities, ensure that apprenticeship programs are up and running efficiently, and attract clean energy project firms and developers.

2. Develop a Climate Investment Playbook

Communities should develop their own Climate Investment Playbooks, with a list of 10-20 concrete projects that implicate different incentives in the IRA. To the greatest extent possible, descriptions of these projects should be carried out through a common template that includes information on project beneficiaries and energy project developers, project location, sources and uses, tax equity opportunities, and economic impact. The goals of such an exercise are several: (a) communicate the kinds of projects that the IRA is likely to propagate throughout the country; (b) create a routine around project description and project financing that can be repeated; and (c) create a community of practice which can take on the breadth of projects envisioned by the IRA.

Investment Playbooks have already been used to great effect with the American Rescue Plan Act, the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act and state funding. Communities as diverse as Buffalo, Erie, Flint, and San Bernadino are using the Investment Playbook tool to tease out priority projects, detail costs and identify funding opportunities. A local or metropolitan Climate Investment Playbook could be a specific outcome developed by a Climate Projects Action Team as outlined above.

3. Add Capacity in Key Organizations

As described above, the capacity crisis in most communities is real and deep. With the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, cities and states have addressed the crisis by engaging legions of grant writers and consultants to help win competitive grants or deploy block grants.

The Inflation Reduction Act is a different animal. It will, on one hand, require more seasoned practitioners at different levels of government (e.g., city, county, and state) and across different types of organizations (e.g., business chambers, CEO councils, economic and community developers, workforce partners) to attract energy project developers by, among other things, orchestrating tailor-made partnerships with apprenticeship programs or community intermediaries so that those developers can boost the value of the tax credits. In these endeavors, the focus must be on amplifying transactions through rain-making and deal-making skills that marry traditional competencies associated with project finance with the specialized incentives of the IRA.

Maximizing the full impact of the IRA, however, requires communities to go further. The IRA will require a new workforce, with skills in a broad array of occupations that range from electrical engineering to EV autos to building-related energy efficiency and renewable energy production. The IRA will also require the provision of new goods and services that can be delivered by new or existing businesses that adapt to the new climate order. While the IRA provides $200M to states for contractor training (primarily energy efficiency), delivering these broader inclusive IRA impacts will require much more funding and close collaboration with community colleges and skills providers as well as business chambers, community development financial institutions and entrepreneurial support organizations, alongside the renewable and efficiency industries. These organizations will require their own burst in capacity to fulfill the vision of the law.

4. Deliver a Marketing Campaign

Cities and counties, in close concert with states, key philanthropies and constituency organizations should devise a major marketing and communications campaign to ensure that existing businesses and resident families are aware of and have equitable access to tax incentive financing. Such marketing is particularly needed around the building-focused renewable credits and efficiency rebates for building owners, including homeowners. Some cities and counties have marketing capacity (e.g., Chicago’s Chief Marketing Officer) or may have done this before (e.g., for the Earned Income Tax Credit, or for the rebates made available through the Obama Administration’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act).

For this IRA marketing campaign, several features are especially important. First, the effort should focus on specific market segments within the community, including those who stand to benefit considerably from the IRA and those who may be least aware of its benefits (for example, LMI families and multifamily owners and small business building owners who could benefit from appliance rebates). An awareness campaign should be layered to include technical assistance opportunities (e.g., helping homeowners fill out what is needed to take advantage of tax credits; helping families see if they qualify for the HEEHR appliance rebates). Existing tax assistance efforts should be scaled to deliver this service and the effort should be optimized for the simplicity of the end user, many of whom may have little or no experience with this type of government paperwork or accounting.

But an IRA marketing campaign must also serve as a business development tactic, reaching and attracting energy project developers outside the community since many energy project developers will naturally work in multiple jurisdictions. Here, the marketing of the very city, itself, must show how the city is built for purpose, networked to help project developers access as many adders as possible, and organized to maximize the full value of IRA incentives.

5. Create a Climate Community Corps

The capacity challenge is so pervasive that it will not be realistic in many parts of the country to bulk up staffing in every municipality or county to serve their own community. Rather, capacity building will also need to occur at a larger geographic scale and work across jurisdictions within metropolitan areas and beyond.

To this end, states or metropolitan areas could establish a Climate Community Corps to help address the capacity challenge, particularly for low-capacity municipalities, counties, and public authorities.

The Corps could be comprised of established practitioners as well as recent graduates of state business and environmental schools. The Corps could be organized and capitalized as a new standalone intermediary. In some states, metropolitan planning organizations could also be a logical vehicle, given their geographic reach.

The Corps can follow the path of other capacity building initiatives. The UK, for example, has created a Cities Climate Investment Commission to help local authorities secure the necessary long-term finance for achieving net zero. The US Department of Housing and Urban Development has had several capacity building efforts over the decades that yield important lessons. University partners, for example, can provide training up front and guidance over time, which can be critical to success.

The Corps can act as a concierge service that acts in the service of regions and helps multiple communities maximize federal funding through smart project design and collaborative partnerships.

6. Innovate on Financial Products

RA initiatives (e.g., Green Banks, ITC enhancements, new Title XVII Debt Product credit authority), coupled with other federal capital initiatives (e.g., the State Small Business Credit Initiative) have the potential to create a burst of innovation in financial products and investment funds. Impact and other private investors are and should grow even farther the opportunity to “dig into the details” and blend financial and social returns in local communities. The Direct Pay opportunity for cities and tax-exempt organizations creates another arena for new and enhanced public/private financing rigor.

Communities should work closely with their states to launch a special initiative designed to capture, codify, share, and scale successful financial techniques and mechanisms as they emerge. The norming of financial innovation will be critical to finance both inclusive clean energy “projects” and new clean tech companies and ensure that gap financing is made available to important end results, whether in the public sector, tax-exempt arena, or energy development/ITC capital stack arena.

In conclusion, the structure of the IRA presents a new challenge for local practitioners. Excellent grant writing, while still important to access the grant portions of the funding (only 9% of the funds in this statute), will not be enough to maximize the law’s economic potential. What will be required is a build-up of capacity and forms of governance that include representatives from a range of sectors, and enable new partnerships between energy project and investment firms and city networks toward social, and not just environmental, goals. These individuals will need to identify distinct local investment opportunities, convene, and harmonize relevant stakeholders ranging from unions to project developers to building and manufacturing owners, and execute in a way that routinizes the practices and financial products going into projects. If this can be done—and we are sure that it can—considerable economic and environmental returns await.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Lori Bamberger is the Managing Director of ABK City Advisors, an inclusive economic development firm. Florian Schalliol is the Founder of Metis Impact, a public and social sector consulting firm. Brian Reyes is a Graduate Research Analyst at the Nowak Lab. The authors would like to acknowledge the leadership and support of the Heinz Endowments.

[1] C40 and Climate Mayors, “The Climate Action and the Inflation Reduction Act, Guide for Local Government Leaders,” October 2022, p. 8. Climate action and the Inflation Reduction Act: A guide for local government leaders (c40knowledgehub.org) Note that this figure is the sum of all the components of the Guide’s charts, as computed by our team, though elsewhere the document describes only $369B in climate-related funding and CBO scoring notes ($391B). https://www.crfb.org/blogs/cbo-scores-ira-238-billion-deficit-reduction.

[2] C40 and Climate Mayors, p. 8.

[3] While these funds to state or local governments provide important dollars for environmental resilience and pollution reduction, this newsletter focuses on the tax incentives, which comprise a far larger portion of the IRA.