In this time of intense polarization, it is rare to find an issue that both sides of the political spectrum can agree on. But small businesses seem to be one of the few exceptions. President Joe Biden has been a vocal champion of small businesses, emphasizing their importance as “the engines of our economic progress… the glue, the heart, and soul of our communities.” And Senator Marco Rubio, who led the Small Business Committee during the pandemic, has repeatedly emphasized the crucial role that small businesses play in job creation and the overall health of the economy. Despite this widespread support, there is still a critical missing piece: a consistent and robust data platform for small, diverse businesses.

Accurate data on small, diverse businesses is vital because it is impossible to deliver adequate and equitable policy solutions to problems that we cannot define. The racial and ethnic gaps in small business ownership are clear and disturbing, with women, Latinos, and African Americans owning only 20%, 6%, and 2% of employer businesses, respectively, despite representing 50%, 19%, and 13% of the population. However, we need more than just broad statistics to understand and address these disparities. If we do not know the number, size, and type of diverse businesses that exist at the local level, we will never be able to provide the necessary funding, programs, technical assistance, and other support services to improve those numbers. Unfortunately, despite the increased awareness and support for small, diverse businesses that emerged from the racial reckoning of 2020, the state of small business data collection has worsened, with a 57% decline in the sample size for the Annual Business Survey (ABS) over the last decade. Granular, timely data on small businesses gains heightened importance as the economy undergoes an industrial transition given the reshoring of manufacturing and the rapid shift to clean energy. Without this foundation, we risk leaving behind communities that are already struggling to keep up.

Since 2021, the Small Business Equity Toolkit (“SBET”) has been a crucial resource for policy and decision-makers seeking to address economic disparities among diverse small businesses across the U.S. Created through a collaboration between the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University, the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth, and Accelerator for America, the toolkit’s Business Index at the metro and city level, provides detailed rankings of Black, Asian, Latino, and women-owned employer businesses based on several key metrics, including business density and average annual sales. This level of disaggregation enables policymakers to target resources where they are most needed. For example, in the Philadelphia MSA, the Business Index revealed that Latino-owned businesses ranked in the mid-range, securing the 44th spot out of the 100 top metros, while Black-owned businesses lagged behind at a distant 77th, underscoring the need for targeted interventions to address this disparity.

Realizing the significance of providing policy- and decision-makers with current information on small, diverse businesses, we attempted to update the Toolkit using the latest (2020) ABS data. To our dismay, we discovered that the latest ABS and non-employer business data had significant limitations that prevented us from conducting our analysis. Our experience highlights a much larger problem – the lack of reliable, timely, and frequent information on small, diverse businesses across the country. This newsletter both lays out the challenges we faced while attempting to update the SBET and offers a series of steps that different levels of government and the private sector can take to remedy these data deficiencies,

The challenge of disaggregating statistics with limited sample size. Tailoring policies and support programs for small, diverse businesses requires accurate data disaggregated by race, ethnicity, gender, sector, and locality. However, this level of precision can only be achieved when surveys, such as the American Business Survey, reach a sufficient number of businesses. The declining trend in the ABS’s sample size is concerning, with just 850,000 businesses surveyed in 2017, a 57% decrease from 2007. In non-census years like 2020, the sample size dwindles to 300,000.

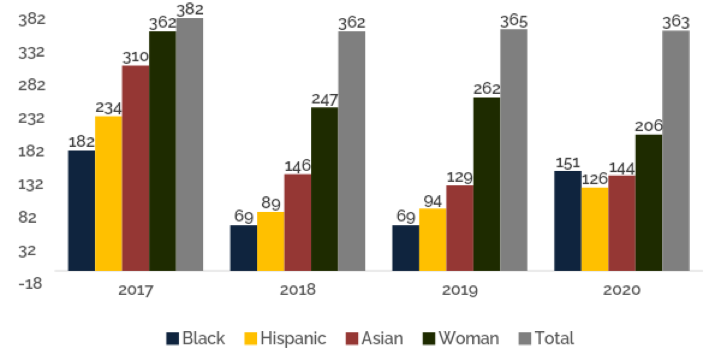

Graph 1. Number of MSAs with business data by year and group (382 in total)

Graph 1 illustrates the consequences, with Black and Latino businesses with no available data for a substantial portion of MSAs in 2017. In between census years, such as 2018 and 2019, data availability is even worse. As table 1 shows, disaggregating data by sector also shows limitations, with data availability limited in approximately 90% of sectors, particularly for minority and diverse groups. Such limitations become more evident in cases like Philadelphia, where data from 2018-2020 shows no Black-owned businesses in retail, food services, and professional services, traditionally the sectors with some of the highest proportions of Black-owned businesses in 2017. This highlights the need for more comprehensive and detailed data to capture the potential for growth or creation of diverse businesses in sectors receiving funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act.

Table 1. Percentage of sectors with no available information by group and year

The challenge with data not being timely. Having accurate and timely data is crucial during times of economic uncertainty, especially for diverse businesses that may require tailored support. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of up-to-date information, as the impact on businesses has been profound and rapidly changing. Unfortunately, the 2020 ABS data was only made public in November 2022, nearly two years after the reference year, and the same delay was seen in the publication of data for 2018 and 2019. Non-employer firms are particularly vulnerable to the lack of timely data, with non-employer firm data only available up to 2018 while employer firm data is available up to 2020. This is especially concerning for Black-owned non-employer firms, which according to the 2018 ABS, made up 96% of all Black-owned firms in the country.

The challenge with tracking performance over years. In addition to the number of firms, employees, and payroll, the 2017 ABS included valuable information on the total sales of each firm, which enabled us to analyze differences in firm size between groups. However, sales information is only sourced from administrative data every five years, and for other years, it is approximated using a statistical model based on employment and payroll ratios. In addition to the approximations entailing a certain degree of error, in years between censuses, this data is reported using flag intervals. The use of approximated sales data and flag intervals limits the usefulness of the data for benchmarking and performance comparisons, making it challenging to identify best practices and areas for improvement in different sectors and ultimately impeding efforts to promote economic restructuring and growth.

The challenge with data and interoperability. To fully understand small business demographics, it’s critical to combine ABS ownership data with other valuable public datasets from the Bureau of Labor Standards, Internal Revenue Service, and Bureau of the Fiscal Service, which provide information on employment and wage data, financial health, and entrepreneurship dynamics. To enable the combination and analysis of data from different sources (a.k.a. interoperability), standardization of data, governance policies, and collaboration between agencies are necessary. Interoperability between state and local agencies’ datasets is also crucial, especially in procurement data, where limited accessibility and data inconsistencies pose challenges to identifying major players in the region’s procurement economy and potential businesses accessing procurement opportunities.

To address the gaps in small business data, we recommend immediate action and coordination from government entities at all levels and the private sector. Collaborative efforts should be made to ensure that small businesses receive the support they need.

In pursuit of this goal, we recommend that the federal government, local entities, and the private sector undertake the following concrete actions:

- Federal Government — Reporting on Small, Diverse Businesses. The IIJA, IRA, and CHIPS acts will provide significant new funding, and it is essential that the federal government includes requirements and resources for data collection and reporting on small, diverse businesses, as well as ensuring interoperability among these data. Fortunately, the Chief Statistician of the United States has convened a Technical Working Group on Race and Ethnicity Standards composed of federal career staff who represent programs that collect or use such data. Their objective is to revise the guidance provided to federal agencies on how to collect and report data in a standardized manner. This effort must be expanded to ensure that data on small, diverse businesses is accurately and comprehensively collected and reported.The federal government is also promoting transparency in small business lending data, as demonstrated by the recent announcement from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) of a new rule requiring lenders to report on small business credit applications they receive, including demographic and geographic data, lending decisions, and credit pricing. To further support small and diverse businesses, the government must incentivize entities beyond the CFPB to meet their needs by promoting data transparency and enforcing regulatory compliance.

- Cities — Modify local procedures for integrating business ownership data into administrative registries. Cities must integrate data on race and ethnicity into their datasets. For instance, including details on the race and ethnicity of business permit applicants can enhance the inclusivity and comprehensiveness of the dataset. Kansas City is already innovating with its small business support operation (Kansas BizCare) and data platform Qwally. Qwally streamlines data collection for small businesses by providing a virtual one-stop shop: Entrepreneurs complete a questionnaire and checklist to register and license their business, giving the BizCare staff insight into their context and enabling targeted support. The platform also tracks interactions and characteristics, helping to identify issues around access and equity.

- State and Local Public agencies — Incorporating Race, Gender, and Ethnicity Data in Vendor and Spending Information. Public agencies have a responsibility to ensure that their spending reflects the diversity of the communities they serve. To achieve this, it is crucial that they develop a framework for sharing vendor and contract data across agencies and make this data available to the public in an open format. This will not only enable better tracking of public spending but also help identify disparities in contracting with small, diverse businesses and ensure accountability for reaching participation goals. The influx of Federal Funds through the IIJA, IRA, and CHIPS act and the Biden administration’s mandate for greater minority business participation in federally funded projects highlights the urgency of this issue. To this end, the Expanding Opportunities for Diverse Entrepreneurs Act introduced by Rep. Joaquin Castro (and broader work he is conducting with the Aspen Institute’s Latinos and Society Program) deserve close consideration.

- Private Sector — Unlocking the Potential of Private Sector Data. Private companies, such as banks, credit card companies, and data analytics firms, have an immense amount of data on small diverse businesses. However, privacy regulations may restrict their ability to share this data. To overcome this hurdle, private companies can innovate by aggregating data and using techniques such as data masking to create interactive dashboards that protect sensitive information while allowing users to explore data. Additionally, partnerships between companies are crucial in gaining access to a broader range of data. Collaborations with other organizations, government and companies can help create tools for the public that provide even more insights for policy makers and decision makers, ultimately driving meaningful change towards a more equitable society.Mastercard is at the forefront of this movement, making their data publicly available through innovative tools like the Mastercard Inclusive Growth Score (IGS). This tool provides a comparative social and economic profile of neighborhoods by blending Mastercard’s transaction data with open-source and proprietary data while ensuring anonymity. The Economic Opportunity Coalition, of which Mastercard is a part, could take a cue from this approach and collaborate to find ways to use their data to help small businesses owned by people of color. By leveraging data-driven insights, the Coalition could better target its investments and initiatives to maximize impact and create lasting change.

The need to support small and diverse businesses is crucial as the United States undergoes an industrial transition. However, the reality is that such support is often just empty rhetoric. The lack of reliable, timely, and frequent information on these businesses presents significant challenges in identifying industries with underrepresented minorities, addressing geographical disparities, and tailoring support programs to tackle specific challenges. In the worst-case scenario, the lack of good data may provide a readymade excuse not to provide the support most desperately needed. Policymakers must prioritize addressing these data limitations if we are to ensure the equitable distribution of benefits from economic restructuring. Without such data, real progress towards supporting small and diverse businesses is unlikely to happen.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Milena Dovali is a Research Officer at the Nowak Lab. Anne Bovaird Nevins is the Director of Economic Development for Accelerator for America