Note: This newsletter was initially published by Governing Magazine on January 17, 2024

Fueled by macro dynamics and unprecedented federal investments, the reshoring of advanced manufacturing is happening at a pace and scale that would have been inconceivable even three years ago. As a result, in many respects the hierarchy of American metros is being reset. If the decade between the Great Recession and the pandemic seemed to be all about “superstar” tech cities, many of the winners in the remote-work era are going to be places that make tangible things.

Metropolitan areas such as Phoenix; Columbus, Ohio; and Syracuse, N.Y., are successfully attracting large semiconductor companies and the domestic and global supply chain firms that serve these advanced industries. Metros including San Diego; St. Louis; and Dayton, Ohio, which have large military bases, R&D facilities and production capabilities, are benefitting from expanded military spending. And a battery belt of next-generation automotive production is being created in real time.

This is a new era of industrial governance. The federal government is playing an essential role as investor and policymaker – for example, by placing new restrictions on high technology exports from China and investments there. The origins of the industrial transformation are global in scale, but its application is decidedly at the metropolitan and regional scale.

For the past several decades, cities and their metropolitan areas were told to plan for a post-industrial future. Now, almost overnight, they are being compelled to deliver an industrial transition of major consequence. The benefits of that transition could be quite high, creating opportunities for a broad array of communities as well as a new set of firms.

To date, most media attention has naturally focused upon the attraction or expansion of large manufacturing facilities, particularly around the production of semiconductors, electric vehicles and advanced weapons systems. Although mega-deals may generate headlines and excitement, they are not sufficient on their own to create the conditions necessary for sustained growth. The reindustrialization of an economy the size of the U.S. cannot be driven by or reduced to the decisions of a small number of major companies like Intel, General Motors or General Dynamics.

The winning metros understand that economic development is not built on a singular transaction, but rather an integrated amalgam of investments. Building networks of public, private and civic players are key to rebuilding a robust industrial base, because advanced industries need many kinds of support to thrive. This means that collaborating across sectors and knitting together investments in a wide range of areas are the core elements of modern competitiveness.

This article is the first in a series that explores the emergence of a new, bottom-up form of industrial governance. The goal of this series is to identify and showcase innovative practices that can be spread across the U.S. in ways that leverage the distinctive advantages of different places. Re-industrialization can and must take advantage of the natural circuitry of metropolitan innovation, where smart practices invented and applied in one place are adopted and adapted by other communities.

This initial article will provide some specificity about the structural nature of the industrial transition itself, the core elements of the industrial ecosystem and the new forms of governance which are emerging. Subsequent articles will then drill down into the specific practices and arrangements that are most promising.

Macro Forces at Play

By all accounts, the U.S. economy is undergoing an industrial transformation of monumental proportions. The forces driving the U.S. industrial transformation, and thus the demand for industrial governance, are large, complex and structural in nature.

Decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the world once again offers plenty of reminders that it’s a dangerous place. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, rising tensions with China, the Israel-Gaza conflict and the complex ambitions of Iran have made the reshoring of production — and the control of sensitive technologies and critical minerals — issues of national security. After decades of offshoring, outsourcing and globalization at any cost, the US is suddenly realizing it needs to make things again.

This paradigmatic shift is having a sizable effect on defense spending and military production. As Ed Luce wrote in the Financial Times, “The world is moving into a new type of great power rivalry.” Defense spending in the United States, and among its allies across the world, is on the rise. Congressional appropriations remain a work in progress, but last month President Biden signed a bill authorizing more than $883 billion in defense related spending this year, which includes funding for a new wave of advanced weapons systems.

As with geopolitical tensions, climate change is also driving domestic manufacturing of a broad spectrum of clean economy goods: the production of electric vehicles and electric batteries, for sure, but also new sources of renewable energy (solar, hydrogen, wind, nuclear), as well as innovations in the electric grid, energy storage, consumer products and green building components.

All these changes are catalyzed by unprecedented federal policies and investments that set the frame for restructuring the national economy – but also require cities and metropolitan areas to deliver what comes next. These massive federal funding measures include the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act, the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act, the $411 billion Inflation Reduction Act and the ever-expanding annual Department of Defense appropriations.

In other words, the US is simultaneously re-militarizing, reshoring and decarbonizing, driven by economy-shaping investments in infrastructure, innovation, climate, manufacturing and defense.

Metropolitan Success Factors

To take advantage of this historic opportunity, successful metros are working across urban, suburban and rural boundaries both within and outside of the main metropolis. The disparate elements of industrial ecosystems — airports, research institutions, community colleges — are naturally located in different parts of metropolitan areas, requiring collaboration and partnership across jurisdictional lines. Given that industrial ecosystems involve talent pools, hubs of research and development and a vast array of industrial players, the metro boundaries often stretch into surrounding regions to capture public land-grant universities, production facilities and defense installations.

The winning metros are organizing themselves to coordinate an eclectic mix of public, private and civic institutions. Radical collaboration is best achieved when it is advanced by an intermediary that is governed and capitalized by a network of public, private and civic institutions. It is not an accident that these metros have entities – Syracuse’s CenterState CEO, the Central Indiana Corporate Partnership in Indianapolis, One Columbus and Greater St. Louis, Inc. – that are built to leverage opportunities and solve challenges on a constant basis.

These intermediaries understand that navigating the new economic order is a game of multi-dimensional chess, with actions needed across all levels of government and sectors of society. These entities often work with other organizations, such as metropolitan planning organizations and manufacturing extension partnerships, to ensure that infrastructure and industrial policies are coordinated to the fullest.

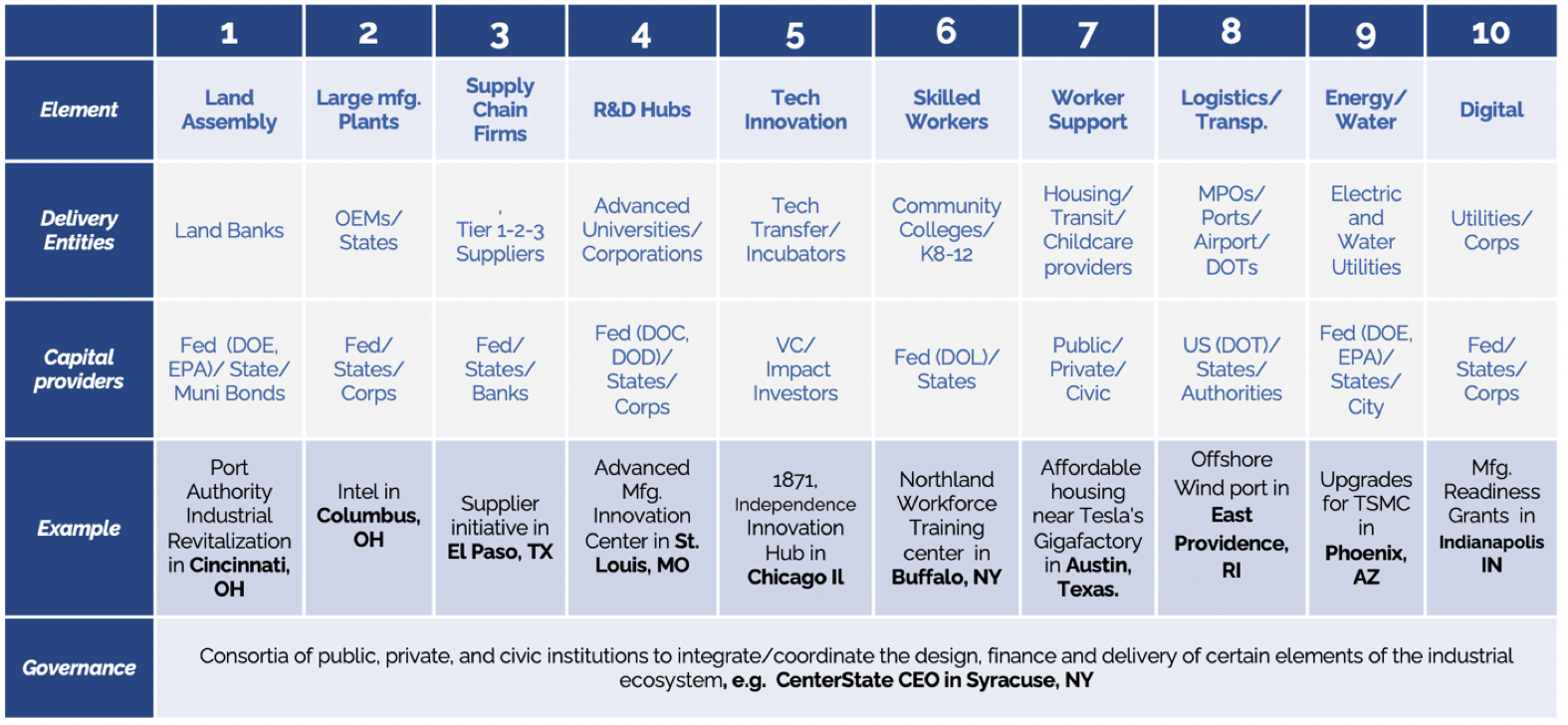

Chart 1: Industrial Ecosystem

Source: Nowak Metro Finance Lab

This chart captures 10 separate elements that, taken together, enable the new industrial economy to operate efficiently and effectively. Each of these separate but related elements involve different public, private and civic entities and implicate different capital providers, as well as stacks of public, private and philanthropic resources. These separate elements rest on a platform of institutions and intermediaries that provide the connective tissue across the entire ecosystem.

These ecosystems naturally include, at a minimum: entrepreneurial support organizations, enabling supply chain firms to locate and expand; universities, providing applied researchers who can continuously assist with product and process innovation; community colleges and labor unions, providing a steady stream of qualified workers who can master the complex nature of advanced manufacturing; transportation agencies, ports, airports and telecommunications entities, enabling the efficient movement of goods, services, data and ideas; public and private utilities, ensuring reliable, renewable and affordable water and energy; and housing, transit and child-care providers, giving workers the foundation for a productive and balanced life.

This industrial transition requires that communities “think like systems and act like entrepreneurs,” to quote Matthew Taylor, the former head of the Royal Society of the Arts in London. Federal programs can be helpful here, providing incentives for the development of ecosystems and multi-disciplinary governance, which many Commerce Department programs — notably, the Build Back Better Regional Challenge and the Regional Tech Hubs competition — are already doing.

But in the end what is needed is a metro-led, bottom up, industrial modus operandi that is built to outlast the programs and incentives of the day. This industrial governance is bubbling in the U.S. and this series will strive to capture its nature and scope as it evolves.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Milena Dovali, a research officer at the Nowak Lab, co-created the industrial ecosystem graphic.