Over the past four months, the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University, The Enterprise Center (TEC), and the Philadelphia Equity Alliance (PEA) have partnered to develop an Investment Playbook for the 52nd Street Corridor in West Philadelphia.

Our goals were ambitious but straightforward. With funding flowing at scale from the federal and state governments and with racial equity commitments made by major financial institutions (see Economic Opportunity Coalition (EOC)), the regeneration of the 52nd Street Corridor is a real-world test of whether large scale resources will actually come to ground, blunt market headwinds, and drive inclusive growth. As written before in our 2019 Community Wealth paper, “mixed-income, mixed-purpose, and mixed-use” corridors can provide opportunities for small businesses to thrive, create jobs for residents, and keep money circulating within the local economy.

The 52nd Street Investment Playbook strives to be a model for transformative community and economic development. It is not a neighborhood plan, but a portfolio of specific projects with specific costs to attract investment from government programs, financial institutions, investors and philanthropies, and a mix of grants, debt, equity, and tax incentives necessary to bring catalytic projects to fruition. The 52nd Street Investment Playbook includes over 30 projects and strategies with an initial estimated cost of ~$160 million and focuses on expanding local property and business ownership and growing locally- and minority-owned small businesses that create good jobs and offer quality goods and services at reasonable prices. Read the 52nd Street Investment Playbook here.

The central role of The Enterprise Center (TEC), a trusted community intermediary, makes this transformation possible. Under the inspiring leadership of Della Clark, TEC is a critical vehicle for federal funding, serving as a Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI), a Community Development Corporation (CDC), a Federal Minority Business Development Agency Center (MBDABC) and a Small Business Investment Company (SBIC). TEC also executes the Pennsylvania Main Street Program on 52nd Street and manages the corridor through the City’s Targeted Corridor Management Program.

Their work builds upon 30 years of supporting Black-owned businesses, leading community development finance, and community planning with organizations like Walnut Hill Community Association. Initially expanding their Retail Resource Network initiative along 52nd Street, TEC has undertaken strategic property acquisition over the past 15 months and recognized this corridor as the cornerstone of their work—an ecosystem that brings together business support and human capital. The role of a visionary steward like TEC is an essential platform for any effort to take a whole-neighborhood approach to commercial corridor development, which prioritizes community wealth-building.

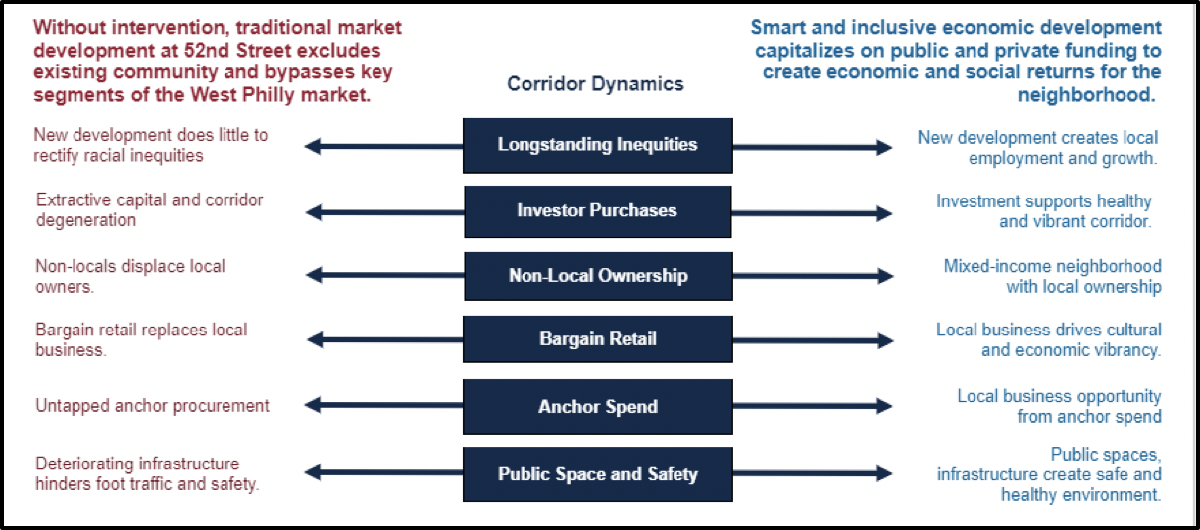

Now comes the critical question: will potential investors invest, and can their impact build wealth rather than extract it? The first test may come soon: The election of a new governor and a more city-friendly legislature could enable catalytic financing of multiple projects and leverage private and civic investments, building on model commercial corridor efforts underway in Charlotte, Chicago, Detroit, and other cities. If the test is met, the funded projects will move away from traditional market development and, instead, will bring economic and social returns to the neighborhood. The result could then be adapted to other corridors in Philadelphia, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the country.

The Current State of 52nd Street

The 52nd Corridor is located in the heart of West Philadelphia. The Playbook catchment area focuses on TEC’s core Main Street service area and stretches for a little over a half mile along 52nd Street from Malcolm X Park (Pine Street) through Market Street (where a SEPTA station is located) to Arch Street.

In the mid twentieth century, the 52nd Street Corridor emerged as an important business and cultural hub for West Philadelphia’s African American community. Known as “Black Main Street,” the corridor included numerous Black-owned businesses and was bustling with jazz clubs, movie theaters, performance venues, local shops and destination restaurants.

Like many urban commercial corridors, 52nd Street has been buffeted for decades by suburbanization, auto-oriented strip development, national discount retailers, on-demand and on-line competition, and pandemic disruptions to workforce, supply chain, and working capital. Still, the corridor continues to play a fundamental role in the life of West Philadelphia residents, with over 130 storefront businesses facing 52nd Street, historic cultural assets, a major public transit station, a large public park and a library.

The 52nd Street Investment Playbook provides an analysis of market dynamics and community trends, emphasizing the attraction of generative rather than extractive investment with place-specific interventions. Our analysis shows that 52nd Street is primed for catalytic investment. Here are some highlights:

- Development Momentum: West Philadelphia is growing faster than other areas in the city, which presents both threats and opportunities. There are over 1,300 housing units permitted for construction between 44th and 57th Streets, with another 1,900 housing units in the pipeline, amidst the highest increases in housing values in the city.

- Neighborhood-supported retail: 52nd Street’s adjacent neighborhood is predominantly Black (74% vs. 39% found in Philadelphia) with lower incomes than the cumulative median income of Philadelphia. Despite the comparative income gap, 38,000 neighborhood residents live within a 10-minute walking radius and spend one-fifth of their income on restaurants, retail, and recreation, making them a solid primary market for local businesses. Cellular data and business survey data suggest that over 60% of the corridor’s retail customers are from the neighborhood, indicating that the corridor is valuable and accessible to residents. This suggests new, affordable, and healthy civic and retail concepts would have strong neighborhood support.

- Adjacent institutional anchors: Penn and Drexel campuses are located within a 2.5-mile radius of the corridor and are home to around 46,000 and 28,000 employees respectively, making 52nd Street proximate to an innovation district. In addition, 52nd Street is one of Southeastern Pennsylvania Transit Authority’s (SEPTA) busiest elevated train stations, where about 6,500 people board on an average weekday.

Our analysis also shows that unlocking these assets for equitable growth requires focused attention on several market levers.

- Minority business landscape: While 74% of the area’s population is Black, estimates suggest that only 41% of total businesses along the corridor are Black-owned. In addition, many businesses occupying street-level storefronts could be classified as “microenterprises.” Creating opportunities for minority-owned retail and service businesses on the corridor to own property, scale retail concepts and tap into the procurement power of West Philadelphia’s concentration of eds and meds is an inclusive growth opportunity.

- Ownership Outlook: As Della Clark often says, “Without site control, you just have an opinion.” Yet four out of ten building owners have mailing addresses outside the city of Philadelphia, and only 36% of housing units in a 10-minute walking radius are owner-occupied. Local owners who are vested and impacted by community vision are key to the health of the corridor.

- Investor Purchases: Over the past five years, new investors[1] have significantly increased their presence as building owners in the corridor. Currently, 16 investors control 40% of the buildings in the 52nd Street area. Most of the buildings that investors purchased were acquired after 2016, with transaction price peaking in 2018 and transaction occurrence peaking in 2020. These trends must be disrupted as quickly as possible to ensure that development is not hindered by potentially speculative investors.

- Building Renovation: Ownership, of course, is just part of the equation. Our analysis uncovered that 25% of the building stock was “below average,” and more than half of the structures on the corridor were “average.” Funding for acquisition and renovation must be combined.

The Enterprise Center’s Plan of Action

Over the past two years, The Enterprise Center has responded to the market conditions described above with a three-part strategy:

- Acquiring and renovating key properties: TEC is focused on acquiring key properties along 52nd Street. Through Transformative Real Estate projects, TEC is generating paths for local, Black business owners and community-serving retail and service businesses that support broader community development goals. In addition, these projects counteract parasitic investment while incubating and preserving tenancy through graduated rents and lease-to-own structures. Currently, TEC is building a permanent office location on the corridor at 277 S. 52nd St.

- Using property renovation to create opportunities for supplier diversity and workforce diversity: TEC deployed a bold supplier diversity and capacity-building program for minority business enterprises (MBEs). At their development on 277 S. 52nd St., they are partnering with LF Driscoll Company to mentor MBE construction and contracting firms in a built-to-suit development with 100% MBE participation. This program deepens firm capacity and develops a robust and qualified pipeline of minority contractors for further construction city-wide.

- Supporting locally owned businesses: TEC is the recipient of the first Neighborhood Economic Development (NED) grant for commercial property acquisition from Philadelphia’s Commerce Department, showing how the grant can be innovatively leveraged to gain site control and convert redundant or parasitic storefronts to productive community use. At 24 S. 52nd Street, the site acquired with the $900,000 NED grant, an $800,000 Health and Human Services (HHS) grant, and TEC equity, a holiday pop-up market was created with over 40 Black-owned vendors, bringing immediate vibrancy to the corridor and supporting MBEs who typically have a constricted market. In response to the pandemic and civil unrest, TEC provided 28 small businesses on 52nd Street with more than $100,000 in civil unrest relief and pandemic relief grants and 50 small businesses on 52nd Street were connected to nearly $800,000 in various relief funds.

The 52nd Street Investment Playbook:

The Investment Playbook scales TEC’s current actions and outlines the priorities of future partners through five (5) cross-cutting strategies for a healthy and vibrant commercial corridor that builds and retains community wealth in West Philadelphia: Each of these strategies is discussed in turn:

- Transformative Real Estate: Through flexible working capital that unlocks solid public-private partnerships, TEC will advance the acquisition and renovation of key commercial properties along 52nd Street. Three of these projects are “in progress” and two are mixed-use “pipeline” projects that would provide incubation space for entrepreneurs, office spaces for businesses, retail space for local minority businesses, and mixed-income housing. For TEC, the acquisition of transformative real estate is a strategy to boost local ownership and to unlock and stabilize properties with the ultimate goal of selling the asset to entrepreneurs.

- Business Support and Attraction: Through grant programs and incentives, TEC will grow and attract neighborhood retailers and incite community wealth by leveraging their existing and proposed suite of business development programs to scale MBEs in TEC-led real estate projects.

- Infrastructure/Public Realm: The Playbook identifies twelve infrastructure improvements and strategies along the 52nd Street corridor to advance community safety, the public realm, digital access, and climate action. As unprecedented funding flows through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), TEC intends to partner with local, state, and federal agencies to fund and implement these projects.

- Community Development: Four strategies focus on prioritizing neighborhood residents for job opportunities, diversifying contractors and construction jobs, collaborating with anchor institutions on income-building strategies, and developing third places for community gathering.

- Housing: As values rise quickly, the Playbook seeks to build in and preserve long-term affordability in the neighborhood through local programs and initiatives that can support the sustainability of local homeownership, improve the quality of existing stock, protect renters, and preserve naturally-occurring affordability.

Next Steps

Realizing the potential of 52nd Street — and commercial corridors like it — urgently requires three moves.

First, the state must invest at scale. For 52nd Street, the initial investment needed from the state is approximately $15 million. As we wrote earlier this year, leftover funds from the American Rescue Plan’s Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund (SLFRF) are tailor made for this opportunity, enabling TEC to acquire, renovate, and stabilize key commercial properties, signaling credibility to the market for TEC to attract subsidized and market-rate debt, additional public capital from city, state, and federal resources, and tax credit-enhanced investment such as New Markets Tax Credit capital. The impact of this investment empowers TEC to continue converting unprogrammed real estate into community-serving real estate that attracts further investment and provides community benefit.

Funding at this level can be part of a broader effort to strengthen Pennsylvania’s Main Street program. The program — of which 52nd Street is part — provides technical assistance and priority consideration for funding like the Local Share Account Program and the Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program. These programs, while important, must grow in reach, scale, and scope. The Main Street program currently supports only 11 areas across Pennsylvania, mostly in small cities; Philadelphia alone has more than 200 commercial corridors. Moreover, these programs’ relatively low award sizes — $25,000 for Main Street planning awards and $500,000 for Local Share Account and Main Street development awards — limit their impact. We believe planning awards of up to $1 million and implementation awards of up to $10 million would be more appropriately sized to meet the needs of commercial corridors.

Other reforms are also needed. Neither program provides the type of flexible, first-in capital needed to develop vibrant and equitable corridors in disinvested communities. Existing programs generally require that applicants have site control at the time of application; without first-in funding to secure site control, existing programs will not live up to their full potential. There is also an opportunity for the state to amplify, coordinate and capitalize efforts to locally empower city neighborhood development offices to offer more financial support and incentives to community-based organizations seeking to acquire and rehab properties for community benefit.

Second, corridor intermediaries and the public sector must partner with private and civic investors. Government alone cannot revitalize the country’s commercial corridors. Coordinated, flexible, and comprehensive commercial corridor development financing is needed for truly inclusive growth.

Commercial corridors represent complex mixes of community assets and uses including small businesses, housing, civic institutions and the built environment. Accordingly, a mix of capital is required. Private sector partners such as financial institutions can focus their Community Reinvestment Act investments through providing capital at scale by pairing grants — which fund pre-development and exploratory activities — with debt serviced by the cash flows from income-generating properties and projects. These different types of dollars — philanthropic and returns-seeking — can be braided together to form a blended capital stack. Blended capital stacks can promote business development, talent development, community services, and the preservation of naturally occurring affordable housing.

To this end, the early involvement of large national and regional depository institutions like JP Morgan Chase, Wells Fargo and Toronto Dominion is a positive sign. But more systems change is needed. In many respects, TEC exhibits a new kind of community intermediary that organizes different kinds of capital in the service of radically different kinds of projects. The future of financing inclusive growth in neighborhoods depends on this.

Finally, the investment playbook approach should be adapted and deployed across similar commercial corridors. Doing so will require intermediaries with the community legitimacy and vision needed to be effective stewards of local corridors. Intermediaries also need the organizational capacity to attract, blend, and deploy capital from an array of sources in service of corridor regeneration. TEC and its cross-cutting development, business support and capital capacities, provides a template to innovate from to meet the multifaceted needs of corridors statewide. Philadelphia’s numerous commercial corridors make it an ideal place to scale the use of investment playbooks.

Conclusion

The 52nd Street Investment Playbook takes advantage of the nation’s “delivery moment,” which rewards communities that get specific and take action. TEC can help transform 52nd Street into a community-serving corridor that provides its residents with high-quality products and services and locally owned businesses with opportunities for growth in a healthy and safe environment. And it can serve as a model for other neighborhoods, as they try to regenerate their commercial corridors in the aftermath of the pandemic. There is a lot of talk about “equity” in the air; 52nd Street could be a model for how it can actually be furthered and advanced.

[1] We defined owners with “CORP”, “LLC”, “PARTNERS” or “GROUP” loosely as “investors”.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University. Elijah E. Davis, Avanti Krovi, Milena Dovali and Bryan Fike are Research Officers at the Nowak Lab.