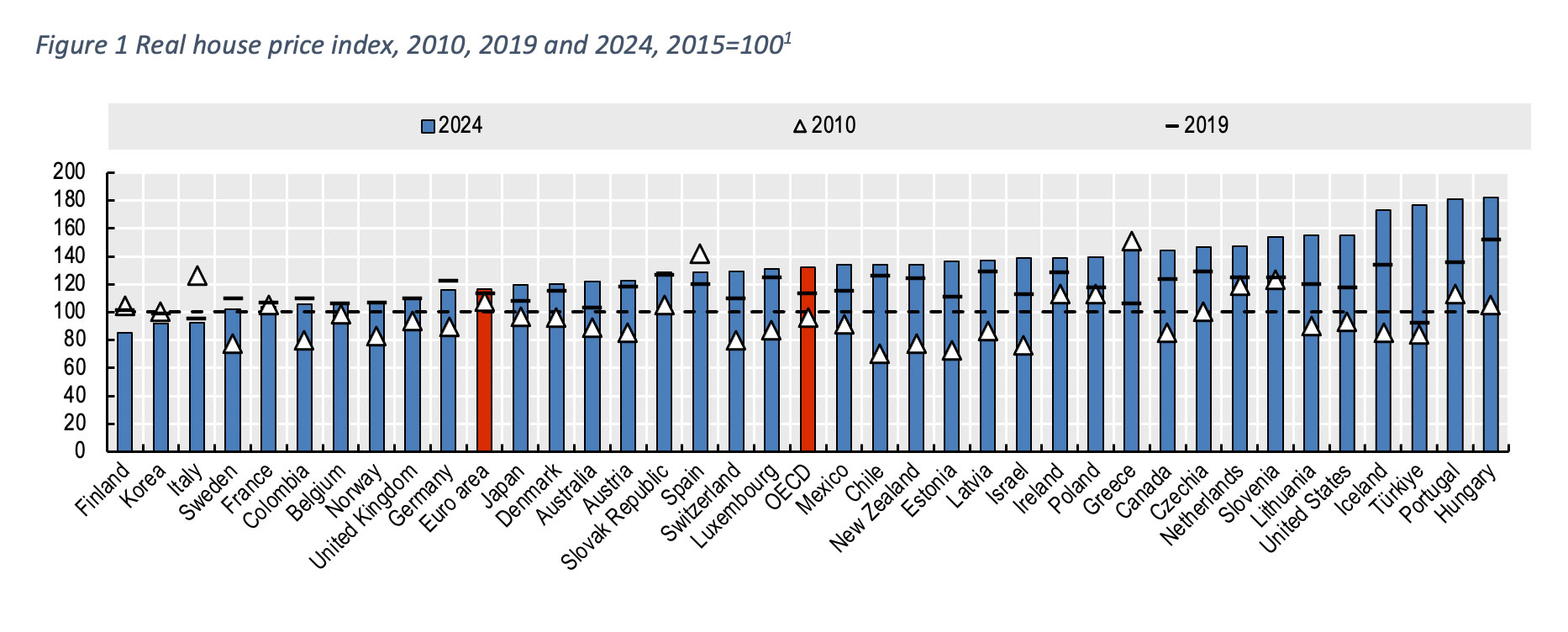

The housing crisis has reached global proportions. Despite significant variation in economic growth, regulatory environments, and level of state intervention, home prices and rents have risen substantially across most OECD countries over the past decade. Figure 1, below, shows that almost all OECD countries have home prices above 2015 levels, with some — such as the United States — up nearly 80% in only a decade. The increase in housing costs is having significant political reverberations. In the US, for example, affordability is the top issue concerning voters as the country enters the 2026 midterms.

Both the EU and US have significant housing shortages. In the US, that number is estimated between 4 and 8 million units depending on the source. In the EU, the European Commission Joint Research Centre estimates the current shortage at 4.6 million units.[1] In both contexts, this requires a significant increase to the overall level of housing production, somewhere between an additional 500,000 to 1 million new units per year above what is already being produced. These additional new units would account for addressing the existing shortage, demographic trends, and obsolescence of existing units.

While the magnitude of the housing crises is similar on both sides of the Atlantic, there are significant differences in both the causes and consequences of these housing shortages. This is partially due to differences in the tenure mixes in European and American housing markets and the comparative generosity of social safety nets. European renters, on average, have a much lower rate of cost burden than the US, largely due to more generous rental assistance and welfare payments. Many European nations have larger stocks of subsidized affordable housing than in the US, even in places like New York City. France, for example, builds more social housing units every year than the number of apartments produced annually through the LIHTC program.[2] The homeownership mix is more varied; while the overall EU homeownership rate exceeds the homeownership rate in the US, some nations, like Germany, have much lower rates of homeownership and a much larger rental sector.

While both the US and the EU are dealing with acute housing shortages, there are nuances, as well, to the political dynamics of those shortages. In the US, more attention is being paid to the rise of institutional ownership and the increasing proportion of single-family rentals. In Europe, overtourism and short-term rentals, along with high vacancy rates due to second-homes and intentional vacancy from landlords, are often the focus of public ire. The regulatory environments differ significantly, with land use, environmental impact, and building codes leading to different sorts of constraints on the building environment. Access to credit and tax incentives for homeowners, developers, and affordable-housing providers also leads to different constraints and tenure mixes. In particular, the response to the Great Financial Crisis produced differing policy responses that have had continued impacts to this day.

The depth of the crises in national housing markets has caused different levels of government to try and address the housing challenges in new federalist arrangements. In the US, the federal government has historically set the policy response with state and local governments implementing these policies. Now, states and cities are devising and implementing their own programs to spur housing production and stabilize local housing markets. In Europe, local governments and housing corporations historically have had much more autonomy to build and manage social housing portfolios, with national governments setting broad financing, tax, and regulatory conditions. Now, the European Commission has, for the first time, a Commissioner focused on Housing and an Affordable Housing Task Force and Action Plan; national governments are also establishing housing production goals, expanding spatial planning, and more strongly regulating housing markets.

What, then, could the United States learn from the Europeans? Given that cities and regions have long had a stronger role in the housing sector in Europe than in the US, it may serve us well to consider their models for affordable housing production, management of their overall housing ecosystem, and use of public assets. At a high level, many European nations are the size of US states. This means that US states could take national models in Europe to the sub-national level in the States and consider implementing policies, programs, and products that Europeans nations have already proven. Local governments in the United States also already have much more fiscal flexibility than their European counterparts, meaning that US cities could raise revenues to finance these new programs. We think that there are a number of specific areas where state and local policymakers in the US could learn from European models:

- Goal Setting and Data: Many European city governments have much higher capacity and are much more engaged in their housing markets. European cities typically set jurisdiction-wide goals related to affordable housing availability and mobilize public resources and assets in service of those goals. They often prioritize data collection and evaluation, allowing them to better understand their markets and address challenges as they arise.

- Public Asset Activation: European cities are leaders in mobilizing their public assets, including publicly owned land and buildings, in the service of housing production. The Copenhagen City and Port model is perhaps the most famous — and has already inspired models in the US like the Atlanta Urban Development Corporation. But it is not the only model. For instance, Amsterdam owns over 80% of the land within its boundaries and has mobilized large-scale redevelopment and land reclamation to expand its housing supply.

- Scaled Housing Nonprofits: European nations have much larger non-profit housing corporations. These housing corporations take different forms in different countries, but some own tens of thousands of units across large geographies. They are active players in their local housing markets, buying, selling, building, and renovating units at scale. These non-profit housing corporations often have sufficient equity and sufficient financial strength to rely on the national government on a limited basis; for example, through mortgage guarantees or low-interest loan programs. Many of these non-profit housing corporations own mixed-income housing developments or cost-based rental portfolios where long-term operations are financially feasible.

- Modern and Varied Construction Methods: European housing production is much more advanced than stick-built construction endemic to much of the US. Industrialized housing production methods (such as offsite and modular housing) is prevalent throughout much of Europe, especially in Sweden, the Netherlands, and Scotland. These methods have the potential to lower the cost of housing production, and the US can and should learn how to create a regulatory and financing environment that increases the uptake of innovative construction methods to decrease the time and cost of housing production.

- A Robust Public and Private Financing Mixture: Europe has a much stronger capital infrastructure to finance affordable housing. Low-cost debt from or guaranteed by the public sector paired with stable tenant-based rental assistance allows for simplified capital stacks. Pension funds and other large investors play a serious role in building for their pensioners and in the wider market. Revolving loan funds and large recapitalization funds like the Danish Building Fund allow for long-term sustainable operations. The US can and must simplify the capital stack to bring down the friction and financial costs to build affordable housing.

In both contexts, new organizations have emerged to try and channel the newfound urgency and shifting institutional arrangements. In the US, the National Housing Crisis Task Force (where we are both Senior Advisors) was founded in 2024 to address the United States’s housing supply and affordability crisis by designing, deploying, and scaling innovative solutions to define the next century of American housing.

In the EU, the Mayors for Housing Alliance was similarly founded in 2024 to provide a mechanism by which mayors can interface with the EU Commission’s Affordable Housing Task Force. Led by Barcelona and with the Mayor of Rome particularly involved, along with the mayors of other cities such as Paris and Bologna, this group of European mayors have formed an alliance to organize an articulated and structured response to the housing crisis. This alliance serves two main purposes: to develop a series of housing-related demands to put before European institutions, and to bring the political initiatives of different cities together in one voice at a European level.

The entrance of the European Commission into the housing space represents a new role for the EU. In December 2025, the EU’s Affordable Housing Task Force released its Affordable Housing Plan. The plan enumerates ten actions that the Commission must take to address the housing crisis throughout the continent, including boosting production, mobilizing investment, driving long-term reforms, and protecting the most affected. The action plan is expected to mobilize EU funding and legislation to help member states address their localized housing crises.

These dual initiatives in an international context provide a clear opportunity for knowledge exchange between the two crises and responses — both to identify where different models are being used and where challenges converge. One example of the convergent challenges can be illuminated with a focus on workforce housing. While the US and Europe use different terminology, there is a growing recognition that the housing market is not working for middle-income households. In the US, there has been a surge of interest in so-called workforce or essential-worker housing. Colorado has established a new Middle-Income Housing Authority, and many cities and states are expanding the definition of affordable housing up to incomes above the regional median. In Europe, social housing has largely been restricted to lower-income households because of an EU directive on state aid. But the new EU Affordable Housing Plan recognizes that this state aid restriction has impeded the ability of national and local governments to support middle-income households in expensive cities and suggests enabling greater flexibility to produce what the Europeans are calling affordable housing — and what we Americans would call workforce or middle-income housing.

The challenge, as always is how to translate European models into the American context (and vice versa). This is a particular difficulty in the current political environment on both continents. Many elected officials, and many voters, are reluctant to import good ideas to the United States if they are European. Additionally, European nations and the United States operate on different scales, with different rules of the game and different distributions of power. It is not so simple to transfer a model from Amsterdam to Los Angeles 1 for 1.

Instead, what is needed is to distill the core components of a European model. These components include the roles played by various organizations, the structure and scale of key operational institutions, the sources and uses of capital, and the enabling regulatory environment. From there, the question is what analogs exist or could exist in the US context.

Nearly a century ago, housers like Catherine Bauer looked to Europe to understand what public housing could look like in the United States, and her findings led to the basis of the public housing system that we have today. Over the following decades, housing policy in the US grew out from a path that was determined by the policy interventions of the 1930s. The developmental path that housing policy has taken means that, though the specific roles and entities may look different across the continents, the core components of European models can be adapted in the US context, even if different players have different roles and powers. What is needed is a clear mapping of the challenges, the solutions, and the ways that those solutions can be implemented at the state and local level in the context of a radically changing federal environment in the US.

Bruce Katz is Founder of New Localism Associates and a Senior Advisor to the National Housing Crisis Task Force. Ben Preis is the founder of Urban Research Advisors, a Senior Advisor to the Task Force, and is based in Amsterdam.