To start off the year we argued that the right question on housing isn’t “what should we do?” but rather “which housing crisis are we solving?” In that piece we identified seven intersecting housing challenges — from zoning reform to construction methods to maintenance and operations— and cautioned against over-indexing on any single one.

As State of the State addresses proceed in earnest, Governors across the country are now proposing answers to this question with agenda-defining proposals. As of this writing, 37 governors have delivered their State of the State (or comparable) addresses for 2026. We reviewed the addresses and found that 27 included a substantive focus on ways to make housing more affordable. There is not one clear policy prescription that Governors are taking to make housing more affordable, but rather a panoply of approaches. Governors are diagnosing different problems, reaching for different tools, and landing in very different places — often irrespective of partisan affiliation.

This is not a failure. It may, in fact, be exactly right and reflects the role that states famously play as the nation’s “laboratories of democracy.” But it also means the emerging patchwork of state housing policy needs a clearer framework if it’s going to add up to something more than the sum of its parts. One risk of the current “thousand flowers blooming” approach to state housing policy is that Governors, caught in the midst of political and economic pressures, may resort to short term salves and partisan red meat rather than a clear strategy to address the housing crisis. This is especially urgent for several reasons.

States Have Increasing Responsibilities: With the federal government deeply polarized, states are being asked to shoulder more of the housing burden. The federal government provided historic increases to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit and extend Opportunity Zones in last year’s tax legislation — but administering these programs falls to states. Congress also appears poised to pass some version of bipartisan housing legislation (though what shape it will take between the House and the Senate versions of legislation still remains to be seen). But reductions in the federal housing workforce as well as uncertainty about key federal programs and policies are taking their toll. State governments don’t have the option of waiting until the dust settles; they are being asked to act now.

Governors Face Increasing Public Pressure: There are 36 Governor races in 2026. Put another way, nearly 3 in 4 governors are facing either elections or term limits this year. With the politics of affordability driving races in many states and housing driving affordability, we should expect sitting governors and candidates alike to offer solutions. Nothing focuses the political mind as much as going before the voters.

Sitting Senators are Going Local: Sometimes these factors collide. Four members of the U.S. Senate are running to be governors of their states – Michael Bennet in Colorado, Amy Klobuchar in Minnesota, Tommy Tuberville in Alabama and Marsha Blackburn in Tennessee. As Senator Bennet recently told the New York Times: “I think what is driving people the other way – what is driving me the other way – is the feeling that the real battle now is going to be in the states, that it is not going to be in D.C.”

Below we try to make sense of the emerging patchwork and suggest some ways to think about a clearer framework for state leaders trying to meet the moment.

Altered States: The Shifting Landscape

The state of state action on housing is radically different than what it was when all but a few of today’s sitting governors took office 4+ years ago. States are on a legislative tear when it comes to advancing housing supply. At the Mercatus Center’s latest tracking of the 2024-25 legislative cycle, state legislatures introduced 412 pro-housing bills and passed 124 of them (this was up from over 250 bills introduced the previous year). In a related analysis, Jenny Schuetz helpfully categorizes the reforms that have passed over the last few years.

These reforms, by-and-large, take a deregulatory bent by allowing more types of housing to be built in more places, setting goals for how to get there, and making the process of building less burdensome. Even in the six months since Jenny’s policy brief, to take one example, California made waves by removing excess environmental review on infill development and then legalizing more types of apartments to be built near transit (with the landmark passage of SB79).

This regulatory-reform picture is partial though. While the legislative landscape has been altered for states, their administrative capabilities have not caught up as quickly – leaving many with large mandates for change and bureaucratic complexity that drives up costs and makes development difficult. In an excellent report, Sarah Karlinsky and Jenna Davis at the Terner Center recently highlighted the depth and variation of the challenge faced by states. Their analysis of how states structure and govern their affordable housing finance systems found that the average state relies on 2.5 separate entities to administer its main affordable housing resources (whether federal or state). This creates all the administrative challenges one would imagine: mismatched application cycles, delays, higher financing costs, and duplicative requirements. And this is just on the “affordable” side of the ledger, to say nothing of the governance and implementation of the broader legislative reforms that many states have recently achieved – which span the full housing market.

Readers should explore the full map of state housing governance structures on the Terner Center’s site.

The Upshot of all this: The political landscape for housing in which governors are addressing their states and legislatures in 2026 is fundamentally altered from when most took office. There is real legislative and public momentum (and demands!) for reform to drive affordability; but also persistent institutional friction on the financing and delivery side, and mounting budget challenges on the operational side. The State of the State addresses reveal how differently governors are weighing these challenges and charting a course ahead.

The States of the States: What they Said

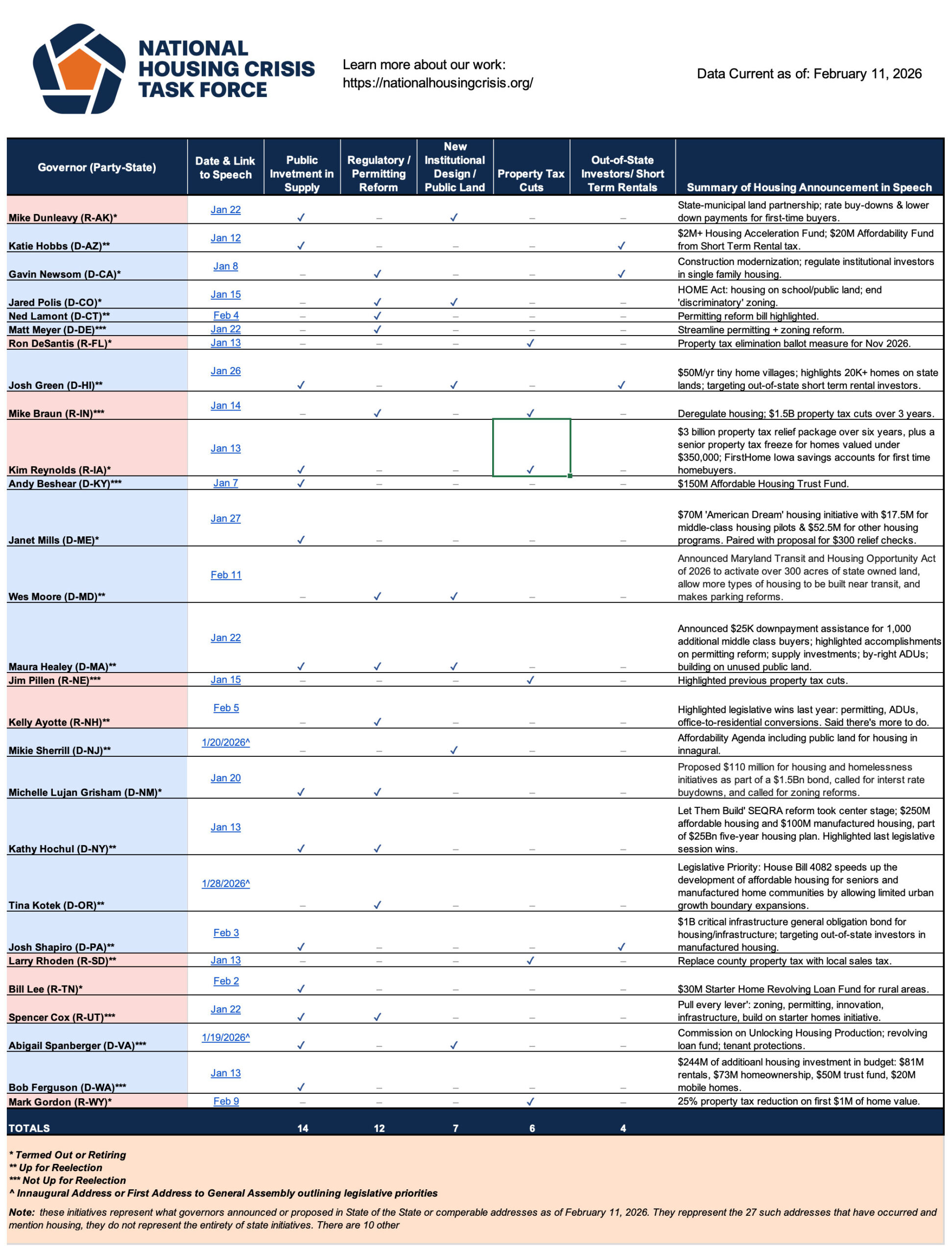

We reviewed the housing content of the 27 addresses that announced some type of housing initiative or agenda (which you can find summarized in the table below). We found they sort into five general approaches to addressing the housing crisis. Some took multiple approaches, but most had one discernable center of gravity.

1. Public Investments in Supply (often) to leverage private dollars

Fourteen governors proposed new housing funds, bonds, or direct appropriations. These ranged from Governor Hobbs’s (D-AZ) proposed $2M+ Housing Acceleration Fund (intended to leverage up private and philanthropic investment), to Governors Spanberger’s (D-VA) and Lee’s (R-TN) proposed revolving loan funds (drawing on successful models in New York, Utah, and Michigan), to the direct budgetary appropriations from Governors Hochul (D-NY) Ferguson (D-WA) and Basheer (D-KY to housing that was part of $1billion+ bond issuances proposed by Governors Shapiro (D-PA) and Lujan-Grisham (D-NM).

Some governors used this opportunity to focus on the construction and finance of starter homes. Specifically: Governor Mills (D-ME) proposing a $70M ‘American Dream’ initiative, Governor Lee (D-TN) proposing a $30M Starter Home Revolving Loan Fund targeting rural areas, and Governor Dunleavy (R-AK) proposing a state-municipal approach for starter homes (more on that below). Many other Governors took broader-brush approaches or packaged funds as part of “affordability agendas” or “agendas to build again.”

Many of these proposals draw from financing models and tools that the National Housing Crisis Task Force has written about – like Revolving Loan Funds, Starter Home production initiatives, and Housing Accelerator Funds.

2. Regulatory and Permitting Reform to make it easier to build

Twelve governors prioritized streamlining housing production through permitting reform and zoning changes. Several celebrated recent legislative victories on permitting and zoning while calling for more action (like neighboring Governors Healey (D-MA) and Ayotte (R-NH). Governor Hochul (D-NY) took the moment to launch a ‘Let Them Build’ agenda centered on SEQRA (environmental review) reform. Other Governors including Meyer (D-DE), Braun (R-IN), Lamont (D-CT), and Cox (R-UT) focused on launching specific permitting initiatives, or pointing at specific pieces of permitting or housing deregulation legislation and highlighting legislative champions. Still others, like Governors Newsom (D-CA) and Hochul (D-NY) pointed at the need to lower construction costs by bringing innovative technology to scale – a role that states are uniquely poised to play. Many of these ideas, similarly, draw from tools that the National Housing Crisis Task Force has written about on industrialized housing delivery and permitting, zoning, and code reform.

3. New Institutional Arrangements and Public Land Activation

Seven governors proposed unique institutional arrangements between states and municipalities, or specifically highlighted ways to activate publicly owned land for housing. Most notable on these fronts were: Governor Polis’s (D-CO) proposed HOME Act for creating state-local partnerships to open underutilized higher education land, nonprofit properties, transit agency sites, housing authority and school district parcels to housing, Governor Moore’s (D-MD) proposed Transit and Housing Opportunity Act of 2026 which aims to activate over 300 acres of state-owned land near transit while allowing more housing types and reforming parking requirements, and Governor Dunleavy’s (R-AK) proposed initiative to provide state-owned public land, lower down payments and mortgage rates backed by the state, for municipalities partnering to build housing and provide long-term tax breaks to first time buyers. Each of these approaches is interesting to us because it fundamentally represents Governors getting creative and thinking of new ways to work with municipalities, harness resources owned by the public, and grow partnerships to build more housing.

4. Property Tax Cuts

Six governors proposed property tax cuts or caps as housing affordability measures (to lower out of pocket housing expenses for owners), though the form and ambition varied considerably. Most dramatically, Governor DeSantis (R-FL) called for a constitutional amendment to eliminate property taxes entirely, on the ballot in November 2026. Others took slightly less drastic (but still dramatic) approaches: Governor Gordon (R-WY) proposed a 25% property tax reduction on the first $1M of home value, Governor Rhoden (R-SD) suggested replacing county property taxes with local sales taxes, and Governor Reynolds (R-IA) suggesting a cap on local revenue growth paired with first time homebuyer accounts. Others, like Governors Braun (R-IN) and Pillen (R-NE) highlighted previous commitments.

We should caution: Property tax cuts or abatements warrant extremely careful consideration. While reducing homeownership (and development) costs, tax cuts also significantly reduce local government capacity to fund infrastructure and services that support housing development and livability. This is a severe tradeoff especially when the more blunt proposals are considered. The National Housing Crisis Task Force has written about a measured approach to “right size” local property tax abatement to help state and local decisionmakers evaluate the tradeoffs.

5. Taking Aim at Out of State Investors and Short-Term Rentals

Four Governors took aim at outside investors and short-term rentals, arguing these forces drive up costs and lock out local families. Each proposed a different angle on market intervention, and similar to our caution on property tax cuts, these approaches need to be evaluated carefully since they run the risk of being too blunt, missing their targets, and harming overall affordability.

Governors Green (D-HI) and Hobbs (D-AZ) proposed reforms on short term rentals, with Green focusing on converting these properties back into long-term housing (specifically targeting out of state owners) and Hobbs proposing a tax on these properties to fund affordability. Governors Newsom (D-CA) and Shapiro (D-PA) both proposed regulating out of state investors, with Newsom hinting at legislation targeted at institutional investors in single-family housing and Shapiro more narrowly focused on limiting rent increases in manufactured home communities to protect residents from investor-driven displacement.

As Mercatus Center research notes though, investor-restriction bills have largely failed to advance in state legislatures despite populist appeal, suggesting governors may find this approach harder to execute than to announce. The political energy around these proposals reflects genuine constituent concerns about affordability, even if the policy mechanisms remain contested.

The State of the States at a Glance

This is a lot to digest, no doubt. To simplify the torrent of information, here is our summary of the State of the States. You can find a the full table in a PDF and go deeper here. And you can learn more about the National Housing Crisis Task Force here.

What Does It All Add Up To?

This diversity of approaches reflects something we argued in Defining Our Housing Challenge(s): there are (at least) seven distinct housing problems intersecting in the United States, and no single reform agenda addresses all of them. A manufactured housing agenda means something different to a governor in a state driving factory-built housing innovation than it does in a state with a lot of mobile home communities. A state with an aging housing stock has different needs than one experiencing rapid population growth. A state with strong construction labor markets is positioned differently than one without.

The risk isn’t that governors are pursuing different strategies. The risk is that, at best, many of these strategies are incomplete on their own and, at worst, pulled from a grab bag of tools with the aim of fixing today’s political and economic problems (without attention to the broader strategy). Funding without regulatory reform can mean expensive housing that takes too long to build. Regulatory reform without funding can mean zoning changes that sit on the books without producing homes. Support for homeowners without supply expansion can simply bid up prices. Tax cuts without a broader strategy for revenue replacement can choke off necessary local services and infrastructure. And market skepticism without an alternative theory of production leaves the underlying shortage unaddressed.

Likewise, across all these approaches, the scale of funding and regulatory commitments matters in almost equal parts to the delivery infrastructure behind them. As the Terner Center’s research makes clear, how a state administers its housing finance programs can be as consequential as how much it spends.

Three Moves for State Action on Housing

As states are asked to shoulder more of the housing leadership mantle, we see three broad categories of action to inform a framework for sustained state leadership on housing. Many of the states highlighted here are working on these actions in some combination (states of the state, after all, just reflect a moment in time of 2026 legislative priorities). Yet we believe the power and ambitions of states in addressing the housing crisis will be fully activated if strategies are built around these three moves.

Move 1: Better Harness State Resources.

Many states are deploying some elements of their existing housing capital, land, and institutional capacity towards building housing and making it operationally sustainable; however, most are not deploying these to get the full effect they could. This means more than adding dollars. It means confronting the administrative fragmentation problem with “strike teams” dedicated to housing affordability. It means leveraging state-owned land and institutional real estate at a state level (as cities like Atlanta have done on the local level). It means setting up creative financing vehicles that leverage private investment, are self-sustaining, and capture value that’s created (as a number of states and cities are exploring). And, it means triaging and defining smart finance for the operations and maintenance challenges present in many subsidized housing programs. Across all of this: it’s not just the scale, but the speed and coordination that matter. Many green shoots are emerging, but they can stretch further!

Move 2: Harness Federal Investments Strategically.

As states are being asked to shoulder more of the housing leadership mantle, it demands that they become more sophisticated federal partners, not less. This means, on one hand, maximizing the impact of resources that have been provided and, on the other, tracking and responding to federal changes.

On the first count: the Tax legislation passed last year made two large housing investments in LIHTC and Opportunity Zones. States, not surprisingly, are already very focused on maximizing the use of low-income housing tax credits. Making LIHTC work is the most common housing strategy in all 50 states and is already absorbing an enormous amount of time and resources by leading agencies. There is still work to do in making these dollars go further to build more housing –as the cost and speed of LIHTC programs varies tremendously by states. States should take a hard look at what’s working elsewhere and aim to replicate it. Less common is having housing agencies participate in the designation and deployment of Opportunity Zones, given that OZs have proven to be a major financing vehicle for multifamily housing. Making housing agencies a key part of the OZ team could not only mean better designation decisions but also the creation of initiatives like Opportunity Alabama that have smartly matched a pipeline of housing projects with locally raised OZ capital.

On the second count: we are in a unique split screen on federal action. HUD has lost a tremendous number of staff since the beginning of the administration but has received substantial resources in the FY26 appropriations bill for key programs like vouchers. Similarly, the Senate and House have both passed different versions of housing legislation with large bipartisan support. Our view is that this legislation will not come in like a white horse to solve the crisis – but it will provide helpful support if harnessed strategically.

Move 3: Allow more housing to be built.

This is, it goes without saying, one of the most important things that a state or city can do to address the housing shortage. It is also, impressively, an area where states have taken a strong leadership role with regulatory and zoning reforms. The experience of states like Montana, Utah, Florida, Massachusetts and Washington, profiled in the National Housing Crisis’s State and Local Housing Action Plan, shows that ambitious reform is possible across the political spectrum, but also that it takes sustained legislative attention, careful policy design, and a willingness to close loopholes and come back for more. Emily Hamilton, Salim Furth, and Charles Gardner at Mercatus lay out a helpful menu of potential options for legislators to consider in 2026 to reach this end.

None of these three moves is sufficient alone. The states that will make the most progress on housing in the years ahead are those that pursue all three simultaneously or in a strategic sequence. The question now is whether state policy can move from a collection of individual initiatives to something more coherent, more sustained, and more equal to the scale of the challenge.

In the end, housing is having one of those rare moments in domestic policy, where there is pressure at all levels of government to address a challenge that has gravitated to the top of voter priorities. For the first time in decades, however, states rather than the federal government will determine whether the country is responding to the challenge at scale and putting in place a foundation for systemic action and impact.

The State of the State addresses illustrate how Governors are, in different markets and across different parties, moving towards something significant and lasting. This is an historic opportunity for change from the ground up.

Bruce Katz is Founder of New Localism Associates and a Senior Advisor to the National Housing Crisis Task Force. Colin Higgins is the Executive Director of the Task Force.